Approaching the magical isle of Bali by air, the traveler is treated to the breathtaking sights of Mount Agung's perfect volcanic cone, a rich green tapestry of paddy fields, and lush wooded hills below, which raise the spirits after the long transpacific haul to Indonesia.

Preformed mental pictures of this tropical paradise (courtesy of Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, and Dorothy Lamour) need modifying if the arrival in present-day Bali is not to disappoint. The peninsula at the island’s southern tip has become one of Southeast Asia's most popular holiday destinations, especially for budget-traveling Australians, who hop on a jumbo jet for the short flight. It is almost impossible to spend time in Bali without being confronted with superb examples of the woodcarver’s craft, much of which reveal the Polynesian influences that have colored this delightful island's crafts over many centuries.

Since the mid-1990s, Bali has been the Australian tourist's budget tropical paradise of choice. Only a few hours' flight from Sydney, thousands of revelers descend onto Kuta for two weeks of sunshine and cheap beer. Middle-income European vacationers seek the calm of Sanur’s azure lagoon, and those with a bottomless bank account enjoy the gilded delights of Nusa Dua’s upscale accommodations.

From budget travelers to millionaires, these tourists brought dollars into Bali, which had positive as well as negative effects. This development had a profoundly negative effect in Candi Dasa, where the villagers capitalized on their gorgeous beach—perhaps Bali’s best— by mining the offshore reef for coral, which was burned to create the cement that was needed to build new hotels. By doing so, they caused the golden sands to wash away!

The building boom transformed sleepy fishing villages into resorts, while money filtered throughout the whole island's economy. A farmer growing snake fruit or ram-butan on Mount Batur's volcanic slopes saw sales increase, while fishermen from the north coast made more money from early morning dolphin-spotting boat trips than a whole day's fishing.

Tourism brought woodcarvers an immense new market for their craft—for both souvenirs and architectural carvings (used to decorate new houses and hotels). Much of this craftwork takes place in woodcarving's golden triangle, bounded by the villages of Mas, Ubud, and Gianyar.

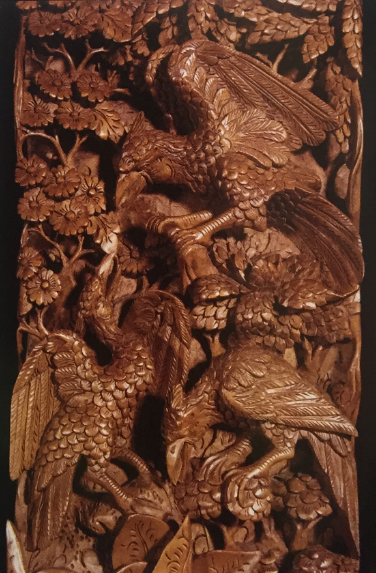

The Agung Rai Museum of Art, part of Ubud's spreading conurbation, features many finely carved doors and decorative panels in both stone and wood, which owe so much to traditional relief carving. For generations, stonemasons have refined their craft for temple decoration, and this museum is a good place to examine this kind of modeling at its finest.

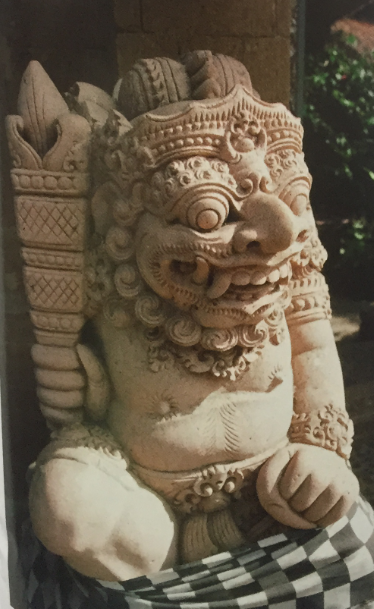

The Balinese are deeply religious people, and many Hindu temples are liberally sprinkled around the island. For centuries, demonic figures (called Totogs-batu and carved in volcanic stone) have been erected to protect temples, villages, and homes from evil spirits.

There is no word that means "artist” in the original Balinese language. A person who carves wood is known as a tukang kayu—a woodworker. This same term is also employed for an artisan woodworker who makes door frames or chairs, or undertakes structural woodwork. Craft skills and a job well done are appreciated, but are seen to fulfill a purpose.

The concept of creating craft objects for their own sake is relatively new. Indeed, the Indonesian word for “beautiful” is never used to describe anything made by the hand of man. The more modest "good" is used instead. Since the influx of Western visitors, this situation has changed, as carvers have been made aware of the commercial and the spiritual value of their creations.

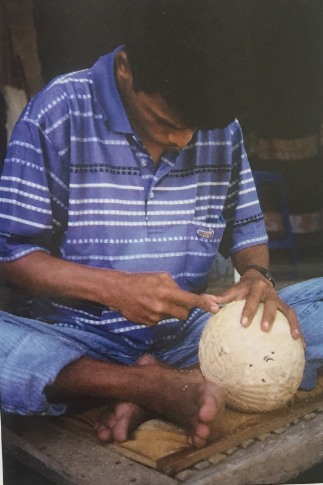

Balinese carving is an ancient art that is steeped in traditions, often mixing magic with skill. Even the tree from which carvings are made is felled according to tradition—with a blessing ceremony preceding cutting.

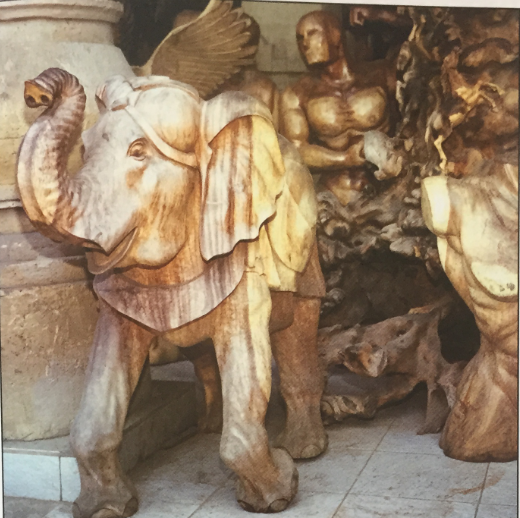

Myths and legends have inspired many generations of carvers, in particular the Hindu epic tales of Ramayana and Mahabharata, which provide a rich source of gods, demons, and more action than a boxed set of John Wayne films. Ornamental woodcarving, sometimes gaudily painted, is often found decorating the structures of homes. The wooden supports of traditional agricultural buildings, like rice barns, are often richly decorated with images of winged lions and mythical characters with magical qualities. While always being decorative, they often have spiritual purposes, serving as superstitious icons to bring good fortune or to ward away evil spirits.

Traditional carving first fell into decline with the arrival of the first Europeans in the 1800s, whose preoccupation with modernity led to many craftsmen adopting a Western way of working. European furniture designed in the nineteenth century often groans under superb ornate carving. Remove the decoration and you have on everyday Western wardrobe.

The year 1938 saw the start of a revival when an applied art school opened in neighboring Java. The academy in Jogjakarta offered training in traditional crafts to boarders from all over Indonesia. When the graduates returned to their villages, they passed on their skills to a new generation of carvers.

In Bali, the arrival of Russian-born Walter Spies from Germany and Rudolf Bonnet from Holland in the midwar years had an impact on Balinese carving, w ic can be experienced to this day. They identified a natural urge to express themselves” in Balinese carvers, recognizing an innate talent, but saw how, by only copying old existing carvings, they had taken a “cultural cul-de-sac” with no route forward.

Spies and Bonnet, settling in the area around Gianyar, encouraged carvers to exploit a lucrative but untapped market by producing works that could be sold to foreigners. Before this time, carvings weren't used as decorative items, so no payment was expected when they changed hands. Carvings simply weren't viewed in a commercial way. This change immediately brought carvers substantial income, while freeing the craftsmen from the creative constraints brought about by slavish copying of existing works.

They also learned to appreciate their raw material by using the natural grain and color of the wonderful woods available to them. Previously, carvers had gilded or painted everything they made, employing a Balinese delight in strong colors. Even today, painted carvings are popular, particularly for cultural or religious events, like religious ceremonies, dances, or funerals.

Limewater colors are often used because they have the additional benefits of halting woodworm and other wood-boring insect attacks, which can be devastating in the tropical climate. This tradition can be seen in every carving workshop or showroom, where among the subtle and refined natural woodcarvings, you can find incredibly garish Garudas and polychromic panels. Often large scale, these carvings usually find a permanent home in hotel lobbies all over Indonesia.

Ubud has long been Bali's artistic capital, drawing visitors keen to absorb some of the island’s rich tradition of music, dance, art, and of course, carving. In the 20 years since mass tourism arrived, the village has grown beyond recognition, from a tiny village above the Monkey Forest, to absorb surrounding hamlets.

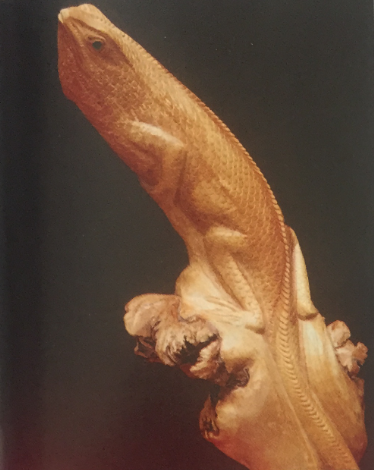

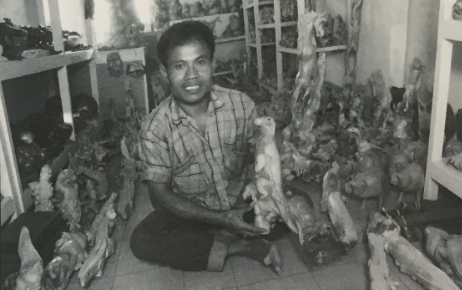

When I first paid a call to the workshop of J. Made Darma 20 years ago, I discovered the master carver at work on his specialty: animals fashioned from what he called “parasite wood.” He explained how the mushroom-shaped growths are found throughout the forest attached to larger trees, often to the chinaberry tree (Melia azedarach). If it is not removed, this mistletoe-like parasitic vine will quickly destroy its host tree At the point of attachment, these malformations, often called wood roses, are darker in color than the host wood and are oddly shaped, making them an ideal timber to carve.

They are self-perpetuating; almost as fast as they are removed, new growths appear. The carver’s challenge is to size up the misshapen lump—no two are alike to see what form lies within waiting to be released by his carving knife. Holding the wood between his feet, the carver works rapidly with his chisel and mallet, incorporating the fungus-textured part (which once held onto the host tree) into his design.

For many years. Made Darma's subject matter was drawn from small wildlife, such as the lizards and frogs that filled the surrounding jungle and forest. “I stopped carving parasite wood in 1999, because I was selling carvings for 15,000 rupiah (Rp.) ($1.50), but the wood was costing me 6,000 Rp. ($0.60)," he told us.

Over the last 20 years, he has trained a number of outworkers (many of whom are close relations) to cater for the increasing demand for his carvings. As a consequence, the work of many carvers of varying ability can be found on the groaning display shelves of his small showroom-cum-workshop. The tourist finds things to be fabulously inexpensive, but the carver finds he works ever harder for less reward. It was no wonder that Made’s son was seeking new ways to earn a living.

In the years since he stopped carving parasite wood. Made has used his talents to create larger birds and animals, including some fearsomely lifelike Komodo dragons—the result of tourist expansion eastward to the reptiles’ homes. “Years ago, people stayed in Bali,” he explained, "but now they go east to Lombok, Sumbawa, and Komodo, where they see dragons (any of various very large lizards, especially the Komodo dragon) and ask me to make them.” Gegirang (Leea angulata) is the wood of choice for these carvings, because as well as taking the knife well, its color varies from pale sapwood to tan near the heart of the tree.

He was scathing about the quality of the carvings that were available in the Pasar Seni tourist art markets. He showed me one 18” long example that he had bought to demonstrate the difference between good and bad carving. "This cost 200,000 Rp. ($20.00), and when people ask why I charge 350,000 Rp. ($35.00) for one the same size, I show them this and they can see why.”

The difference, of course, was in the quality of the carving, which is an amalgam of technique, creativity, sensitivity, observation, and “a magical sprinkling of fairy dust" that transforms a block of wood into a living thing.

I was heartened to see how, with passing years. Made's carving had improved along with his command of English, but the substandard market-bought sample he disparagingly displayed was against all Balinese tradition. In the past, even when pieces were created at a low price for the tourist market, it was rare to find a poor-quality carving.

The Balinese tradition of pride in one's work meant that the carver would lose face if his work wasn't at an acceptable quality. Some of today's carvers had obviously discovered that tourists often saw only the price and were oblivious to quantity, so some workers had obviously started to work to market-driven standards.

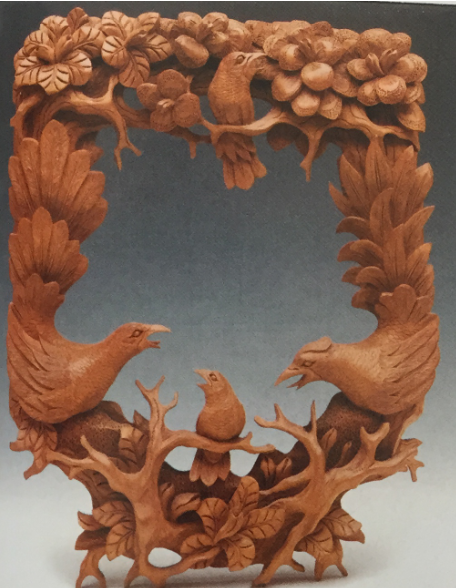

A hundred years up the hill, Merta Nadi's shop is a newer addition to the Monkey Forest Road. He specializes in panels carved in deep relief, often from wood 3 inches or more in depth. He marks mainly with kepelan wood (Mangietia Glauca), which is in the magnolia family and ideally suited to deep-relief carving.

Like many other carvers in this tradition, Merta undertakes decorative panels illustrating scenes from the Ramayana, but these are commonly found in Bali— his bird-themed picture frames and mirror frames, however, are unique.

Merta’s deft touch has revealed a beautifully balanced scene of birds set among twigs, leaves, and flowers— all executed with precision and verve. It would be very easy for this kind of work to go over the top, but the balance and the delicacy of the composition and carving are irresistible. The price of this perfection was 450,000 Rp. ($45.00)—even if the price had been five times as much, it would have been a bargain.

The smaller $20.00 frame is a masterful composition of parent birds framing a youngster, and the carving is of such a high quality that the sex of each parent bird is identifiable. The ornate tails fan upward to the upper part of the frame, which shows another youngster sitting among beautifully formed leaves and buds.

Both frames are rabbeted to accommodate a mirror or picture, although reflections can cause the already ornate frame design to become a little muddled.

While Ubud has long been the commercial center for woodcarving, the craft's real heartland lies in its satellite villages, whose products have now reached a world audience thanks to Internet marketing.

A ribbon of houses, workshops, shops, and guesthouse link Ubud through the villages of Padangtekal, Penqo sekan and Teges to Mas. Teges, once a quiet cross roads dotted with small workshops, has grown into < major wooqcraft center. Here, furniture makers compete for space with woodcarvers, some of whom work in cottage industries; others work in more impressive scale from roadside workshops. This is most appropriate, because in Bali, the word Teges is commonly used for the woor we know so well as teak.

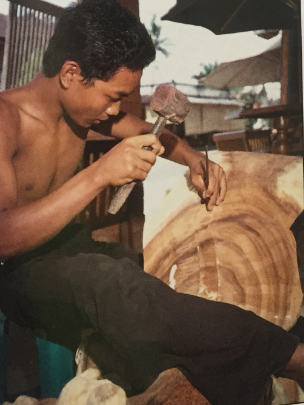

Teges in Bali's free-form carving center, where three-foot-high eagles raise their wings over half-hewn horses from tree trunks, awaiting the master carver's torch. Whille these landmark pieces act as advertisements to draw in passing tourists, unlike in previous years, evidense of carving in progress was less easy to come across on my most recent visit.

This style of carving first started to be developed in the ous, notably by Ida Bogus Nyana and the Cokot family. The twisting forms of kendal wood (Cordia dichotoma) was often preferred, as its natural contours a owed fabulous twisting compositions. Sections of a .low frooic often five or six feet in length, were left outside to weather for a few seasons before the carver used his skill and imagination to reveal the convoluted designs he saw within the wood. Today, Jepun Bali (Plumeria acuminata) and gegirang woods are also used, although the time-consuming process of weathering is not so popular.

Mask carving brought the small village of Mas to the attention of carving lovers. The Balinese are playful people who are eager to enjoy public celebration of any event with dances, which are an important part of Balinese culture. During the Galungan festival (a ten-day celebration of the death of legendary tyrant Maya-denawa), mythical lion-dog creatures called Barongs prance from temple to temple—heavy, carved wooden heads test the dancer’s strength.

No celebration or ceremony is complete without a dance, so many villages around Ubud now offer regular daily dances to satisfy tourist culture-seekers on coach tours. Each dance requires its own masks, bringing additional work for the carver, perpetuating the mask-carving tradition, revitalizing dancing skills, and providing an income for the gamelan orchestra musicians who provide musical accompaniment to these events.

Carvers, such as I.B. Sutarja, have felt the benefit of this boom, and Sutarja’s showroom displays a wonderful diversity of high-quality carving undertaken not just by him, but by his children who carve in their own styles.

The mythical bird known as Garuda is ubiquitous throughout Indonesia, from carvings perched on ancient temple roof beams to taking pride of place on the Republic’s great seal. This great eagle-like creature is a popular national symbol, representing God as the preserver and maintainer of life. Typifying Bali's charm, the fantastic nature of this creature’s mythology leads to flights of imagination by the carver, featuring outlandish and colorful decoration.

A vibrant Garuda mask, eyes popping and teeth protruding menacingly particularly impressed me. Carved by Mr. Sutarja, this had been decoratively painted by his daughter, who applied the finishing touches with gilded pierced leather and horsehair. Often, the painting can take much longer than the actual carving and push the price well beyond the souvenir market. In the past he would have quoted prices in rupiah, but today the dollar is his currency of choice. This piece had a starting nrice of $600.00, although hard bargaining would no doubt have substantially reduced this figure.

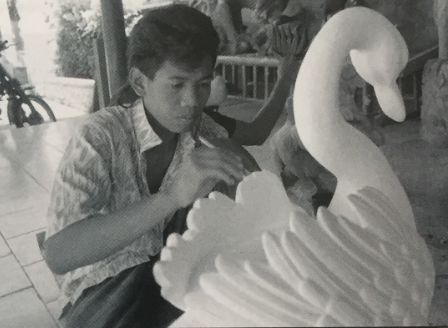

One carver who has gained an international reputation for his representations of Balinese birds is Ngurah Umum, “The Duck Man of Bali.” Ngurah has a sizable workshop in Gianyar. His own carvings have been widely exhibited, but he heads a team of carvers who can be seen during guided tours of his workshops chiseling, cutting, finishing, and painting the large lifelike pieces that have become his studio s hallmark.

Ngurah's showroom is part museum and part shop, containing such special pieces as a wonderfully carved three-by-two-foot panel saucily depicting maidens bathing. The highlight has to be an exquisite free-form representation of two birds carved from a single piece of wood. The relationship between the birds, the delicacy of the carving, and the contrast in textures and form make it a visual wonder. Looking as if it is modeled by a master sculptor from clay, it has to be one of the most accomplished carvings on the island.

This style of work, formed from a single piece of wood, is characterized by smooth, polished wood set against contrasting textured and patterned areas, which separate elements of the design. Guided by shapes that Ngurah discerns within the wood, he allows his imagination to determine the design, which in the pieces with a mythological theme, are astoundingly complex from a distance—the story only becoming clear with closer inspection.

He also undertakes bird carvings in this style, and one, featuring three sea eagles, is the result of many months of detailed carving. When a single incorrect stroke of the knife could undo so much work, its price tag of almost $4,000.00 reflects his investment in time and skill.

While lower-cost items, like masks for the upstairs showroom, are produced by his team of carvers, much of Ngurah's own work falls into the higher-price range. He concentrates on finer, more time-consuming pieces, combining polished free-form bases with delicately carved and painted ducks, often in flight or animated posture.

Ducks abound in rural Bali in the irrigation channels between terraces, flocking on newly harvested paddy fields or being driven along the road by medieval-like drovers. Most of Ngurah's ducks are worked in light, straight-grained pule wood (Alstonia scholaris), a timber also favored by mask makers.

Pule wood is best known as white cheesewood, a very appropriate name, as it easily takes a knife and hold’s fine detail. As I discovered later, it also takes in water from the island's humid climate.

I went with the intention of buying one small duck, and left many dollars lighter and a few pounds of baggage heavier with a small Vietnamese duck eight inches in length and a wonderful 15" long green-headed duck. As with fine masks, the carving is simply a precursor to detailed painting with coats of acrylic paint, upon which feather detail is built up stage by stage. The final effect creates relief as powerful as if it were carved, casting shadow to lift feathers away from the body or texture so realistic that you could imagine drops of water rolling off.

As well as spurring a cultural revival, tourism has revitalized Bali’s temples. Directly and indirectly, visitors have funded restoration of its many temples. Even away from areas on the tourist trail, wealth previously generated by tourism is being reinvested in the cultural infrastructure.

Because religion is so intertwined with daily life, increased incomes mean that once a house has satellite TV and a new motorbike, the temple is next to benefit. Batur Temple, on the rim of the volcano's crater lake, is a huge complex, covering many acres. Around the perimeter, a host of small shrines are protected by heavy doors that are carved and often gilded. Most of these carvings are figurative, showing scenes from Balinese or Hindu mythology, or use the islands flora and fauna for decorative effect.

Bali's climate prevents the formation of what we know as a rain forest, but its soil produces almost 40 different trees of interest to the woodcarver. For the last 30 years, the government's department of forestry has been planting seedlings in Bali’s national parks to supply villages with young trees, encouraging sensible and renewable management of the island's resources. Trees are often revered as the home of spirits and demons, and it is common to find their bases wrapped in a checkered cloth.

The terrorist campaign, which reached Bali in 2002 and was most recently evident in the July 2009 Jakarta bombings, has had a negative impact on tourism, but the development of Bali's woodcarving industry since the arrival of mass tourism, allied to a centuries-old carving tradition, seems to indicate a healthy future for the island’s many craftsmen.

Note: Naming the woods is confused a little by each locality having its own names for trees. Even in the same area, the same wood may have a half-dozen names! For more information about the wood types, please contact the author.

Neil McAllister is a professional writer and returning contributor to Carving Magazine.